When C-SC alum Josh McGhee (’13) was a kid, his dad would often come home from work with a stack of printer paper, each sheet adorned with a photo of a cow on the back.

“What kind of story could you tell about the cow?” McGhee asked himself. And so, he got to work, writing 100 different stories about cows.

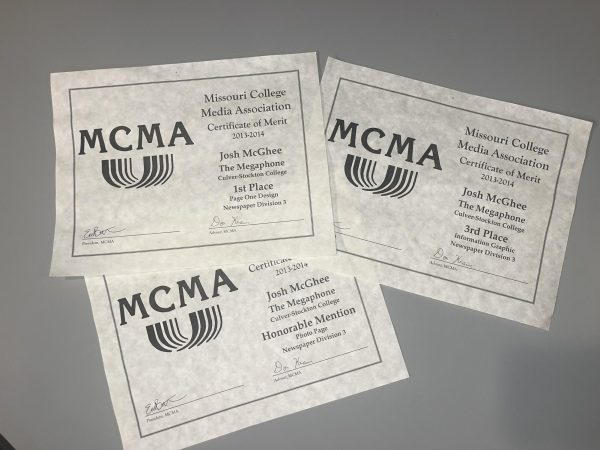

Now, McGhee is an award-winning investigative journalist covering the intersection of criminal justice and mental health at MindSite News. Those who know McGhee describe him as curious, creative, level-headed and sociable.

Sitting for an interview at a Corner Bakery, he came dressed stylishly in a neat green sweater and a long gray coat, his nails clean and well-manicured. He spoke casually but thoughtfully while sipping on his chai latte.

McGhee said he was not always such a social person. He described his younger self as standoffish and solitary. Although he was athletic and played basketball, he spent a lot of time alone, soaking up information.

“I was a kid that loved the library,” said McGhee. “So that’s one thing that kind of never changed, was always the reading.”

McGhee grew up in Tinley Park, a south Chicago suburb with a primarily white population, per capita incomes higher than the broader Chicago area and high levels of educational attainment.

McGhee and his two siblings were some of the only Black kids in their neighborhood; the only other McGhee knew was the son of a prominent local lawyer.

“It’s a very small place for Black kids to grow up,” reflected McGhee.

He and his sister were the first Black students to graduate from his private elementary school. McGhee described growing up in this environment as growing up in a cocoon; his graduating class from eighth grade was only 14 students.

At the same time, McGhee benefited from small class sizes and individual attention from teachers.

“My love of learning and education was kind of fueled by teachers who really wanted to believe in me,” said McGhee.

He described snow days spent, not at home, but at teachers’ houses.

Years after his grade-school teachers instilled in him a love of education, another teacher decisively influenced McGhee’s journalism career.

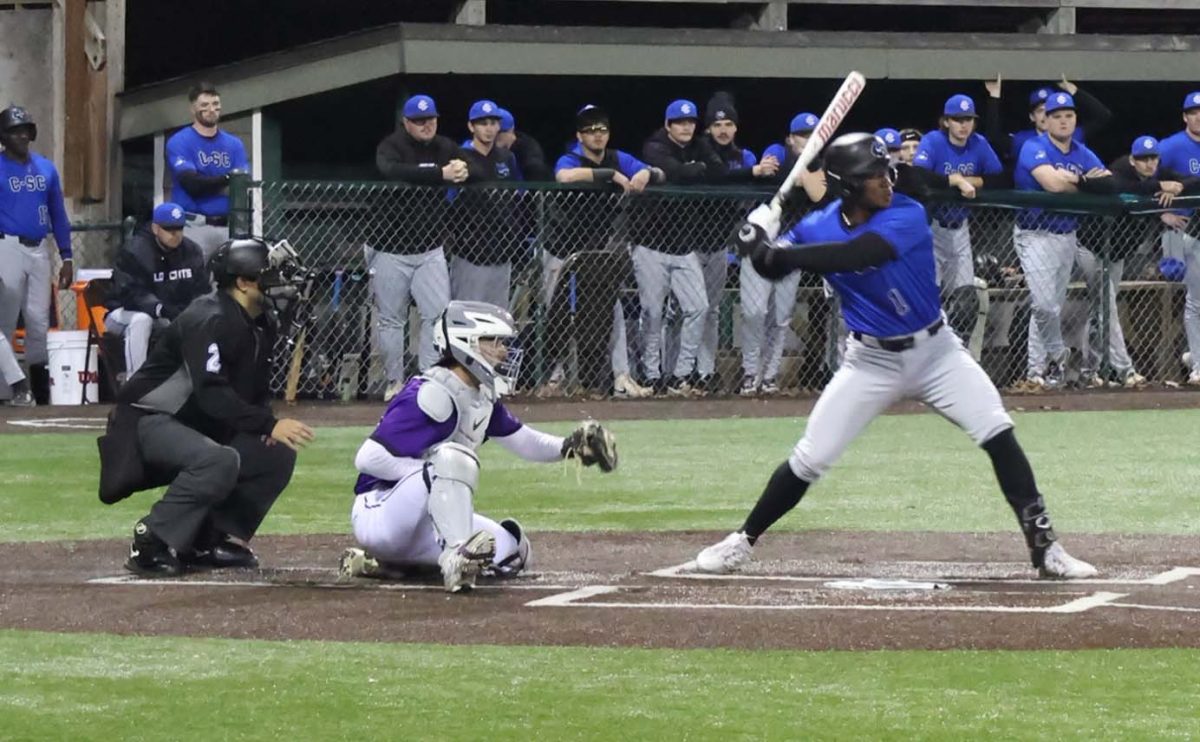

McGhee attended Culver-Stockton College. It was one of two schools he considered, both chosen because he could play basketball there. McGhee majored in communication because it seemed easy and flexible, and because he liked writing.

In his junior year of college, Communication Professor Tyler Tomlinson told McGhee that he needed to be in class to meet then-Chicago Sun-Times journalist, Pulitzer Prize recipient and college alumnus Mark Konkol.

Tomlinson said that he knew it would be a great opportunity for McGhee to see someone who he could relate to — coming from the same small college — finding success.

“I wanted him to experience that, and I wasn’t afraid to shake him a little bit and tell him he needs to get his butt in gear and get in here,” said Tomlinson.

McGhee did not show up.

“I got a call from (Tomlinson), and basically, he was like, ‘You need to get down here,’” recalled McGhee. And so, he rolled out of bed, ran to class and met Konkol.

McGhee asked Konkol how he could get an internship at the Sun-Times; Konkol told him he would not get one. However, Konkol had McGhee send in his resume anyway. McGhee must have impressed Konkol — he got an interview and then the internship.

After his Sun-Times internship, spent working undesirable weekend shifts and learning to write leads, McGhee graduated college and began working the homicide beat at DNAinfo.

Knowing the south side from weekends spent visiting family as a kid, McGhee was equipped to fill the role. He understood that there was a certain look, style, and demeanor to a crime reporter. He described wearing gym shoes with his dress socks; he had needed to run from a scene before.

“You know, you don’t want to be a person who’s dressed up in a suit, coming to a grieving family on the south side of Chicago — you’re not an approachable person, you look like somebody who stands out,” said McGhee. “But you also don’t want to look like the guy who could have committed the crime, either.”

Eventually, McGhee was one of the few people reporting on homicide, and families started to reach out to him. He spent Friday nights sitting at home in a dark room listening to recordings of interviews about loss. Though the stories were heavy, McGhee said he tried to find the joy in each one as “a gift to the family” who allowed him to tell the story.

McGhee also said journalism allowed him to pose questions that others do not get to ask.

“It’s like you get this fake license to just ask questions, to do random things, to be random places,” said McGhee.

While other people are going to and from work, who else but journalists can go into a federal building, can talk to people protesting, can see people’s lives changed forever, McGhee asked.

Throughout the intensity of his reporting, McGhee found support in the journalism community, particularly the Chicago chapter of the NABJ where he currently serves as secretary. McGhee described his relationships with other Chicago NABJ journalists as being like siblings.

McGhee’s friend and former colleague Olivia Obineme similarly described their relationship as familial, laughing and emphasizing her one-year age advantage over McGhee.

Just as McGhee is a product of community support and mentorship, he now gives back by mentoring other young journalists through MindSite’s partnership with Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism.

“I think that’s something that he wouldn’t be doing if it didn’t really serve an overall purpose,” said Obineme. “I think he sees his approach as always leaving them with something useful.”

News consumers and young journalists alike are lucky to have McGhee on the job, according to Tomlinson.

“For those that care about journalism, I would say you have the right guy covering the stories,” said Tomlinson.