Ukraine In Twain – First International Issues Roundtable Discusses Ukranian Crisis

On Thursday, January 27, Drs. Hotle and DeWaard hosted the first installment of the International Issues Roundtable in The Lab, an ACE event discussing the Ukraine crisis and the larger context of international crises. A program of the departments of History, Political Science, and Religion, the roundtable also served to promote the new International Studies major/minor.

Sponsored by Tau Kappa Epsilon (TKE) and Young Americans for Freedom (YAF), the roundtable follows on the Afghanistan series, which discussed the history and political climate of Afghanistan in the wake of America’s military withdrawal from the nation, this event continued the professors’ quest to institutionalize a forum for discussion of and education on significant world events. For those who missed out on the lecture, a summary of its main points, and some additional context follows below.

The professors first spoke broadly on international systems of diplomacy and the motivation of nations, and their leaders, before moving more specifically to the ongoing diplomatic crisis in Ukraine. After laying out the basics of our current era of formal peace between the world’s foremost powers, DeWaard highlighted the irregularities of the conflict in Ukraine, a conventional, international conflict in an era where most wars are civil, asymmetric conflicts within the boundaries of one nation.

DeWaard outlined the theory of Structural Realism, a way to look at international events which allows one to use systemic features of nations to predict and explain the conflict and competition that arises from an unequal distribution of resources. These inequities lead to nations creating arms to secure themselves from competitors and rivals, creating dilemmas for their neighbors in a zero-sum game where the increase to one nation’s security is a threat to its neighbors.

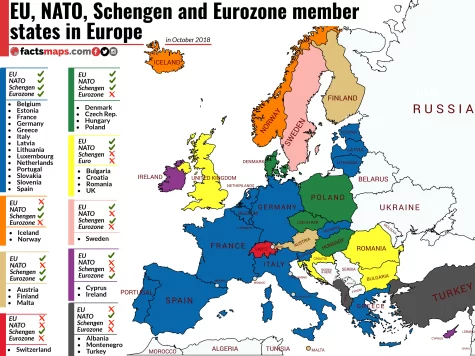

Applied practically to the potential conflict in Ukraine, this lens holds that Russia, an autocracy is inherently threatened by Ukraine’s attempts to cozy up to Europe’s tightly-knit democracies bound by institutions like the European Union and NATO, which surround its western border. Russian leaders like Vladimir Putin seem to fear that the tide of democratic, egalitarian values that has spread through much of Europe will continue to Russia and prompt the people to depose its government, as happened to Ukraine between 2013-14, sparking Russia’s initial incursion into the Crimean Peninsula and the Donbas region.

With its history handled by Hotle, the professors laid out a basic overview of Ukraine. A nation primarily located upon a flat, indefensible grassland, it has passed through the hands of many nations in the last few centuries, from Poland-Lithuania, to the Austrian Empire, most recently into the hands of Russia prior to its breakaway as an independent state after the first World War, though it would soon fall under the control of Soviet Russia a few years later, remaining a part of the Russian state until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989.

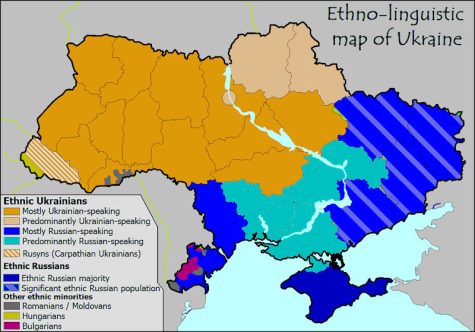

Kyiv, or Kiev, as it is commonly translated, the capital of Ukraine, is held as the cultural birthplace of the Russian people, to the point where Putin often refers to the nation as “little Russia”. Ukraine is a bilingual nation, with its people speaking their native Ukrainian language, as well as Russian interchangeably, though the Russian language holds a de facto position of dominance, much as English or Spanish would in the UK or Spain’s former colonies. As DeWaard asserted, while Ukrainians can speak their own language as they like, Russian speakers know that they understand Russian.

Putin justifies actions against Ukraine through claims that he’s protecting the Russian-speaking population from oppression by the Ukrainians asserting their own culture and nationalism. However, this largely disguises the political motives that underly the split. The Russian speaking population of Ukraine, thought to make up about 20% of the country, according to the professors, is more inclined towards friendliness, or even reunification with Russia, as has been enacted in full in the Crimea, and de facto in Donbas. Meanwhile, the Ukrainian speaking portions of the nation turn to the EU and NATO, the influence of the United States to maintain their independence and assert values consistent with the nations to their west.

While Russia looks back to Ukraine’s use as a staging point for invasions in the Napoleonic and both World Wars, Ukraine recalls national tragedies such as the Chernobyl disaster, or the Holodomor, a famine under the Soviet Union, the predecessor to the current Russian Republic that led to more than six million deaths, alongside their time subjugated by the Russian Empire, on whose traditions Putin draws to legitimize his rule.

Ukraine today is in quite a poor position, with a government that has spent years riddled with scandal and corruption, having elected as their President a politician who rode his performance as the President of Ukraine on a TV satire to the real office. Even with military support from NATO, Russia’s army remains much larger than that of Ukraine’s, even if Ukraine maintains one of the largest armed forces in Europe, facing threats on five fronts. Belarus, their northern neighbor, with similar cultural ties to Russia, and a pro-Putin autocrat at its helm, has allowed Russian troops to deploy along Ukraine’s northern border.

The possible war between Russia and Ukraine follows Russian intervention in Kazakhstan, another breakaway from the Soviet Union, and its threat to deploy troops in support of Belarus’ dictator in the face of popular protests earlier this year, these conflicts perhaps having stoked some sense of insecurity that has prompted the current invasion. Much as the United States might grow unhappy if an unfriendly dictator were to rise in Mexico or Canada, the prospect of a democratic government being instated in the little autocracies that surround Putin’s dictatorship show an alternative to his iron-fisted rule which he likely feels cannot be permitted, unless he wishes to find the same crowd of protestors smashing down his own front door.

If one wishes to know more about these events, the professors suggested that students consider their newly minted International Studies Major and Minor programs. Two further events in the series are slated for February 24, and March 31, the last Thursday of each month.